INTRODUCTION

Up until this stage, our discussion around introductory paragraphs has mostly been on how to write a quality thesis statement, since it is the central point around which the rest of your essay is built.

It is now time to consider the sentences leading up to the thesis statement; the sentences that will actually form the majority of your introduction. These provide background statements that tell the reader why the thesis statement is important; in other words, why the essay is worth reading in the first place.

While the thesis statement provides an essay with purpose, the sentences before it explain why that purpose matters.

METHODS OF DEMONSTRATING IMPORTANCE

There are many different ways of demonstrating importance; for instance:

- Quoting a statistic that shows some sort of significance about the topic (e.g., many people are affected by something, a large amount of money has been spent, there is a high uptake of something).

- Describing the effect that the topic has on humans, or on other living things (these could be physical, psychological, emotional, financial or personal effects).

- Highlighting a time-sensitivity that requires quick action to address (e.g., action or inaction on this could lead to consequences).

- Describing how the topic is central within a broader area of study, or how other things depend on it (e.g., if we get better at A, we will also be able to do B and C better).

- Raising a question that is worth knowing the answer to (e.g., what effect will it have, if we do things this way rather than that way?).

It is important to note that it is not necessary to use all of these in a single introductory paragraph. You would select one or more methods that are appropriate to the topic that you are writing about.

MAKING YOUR CASE

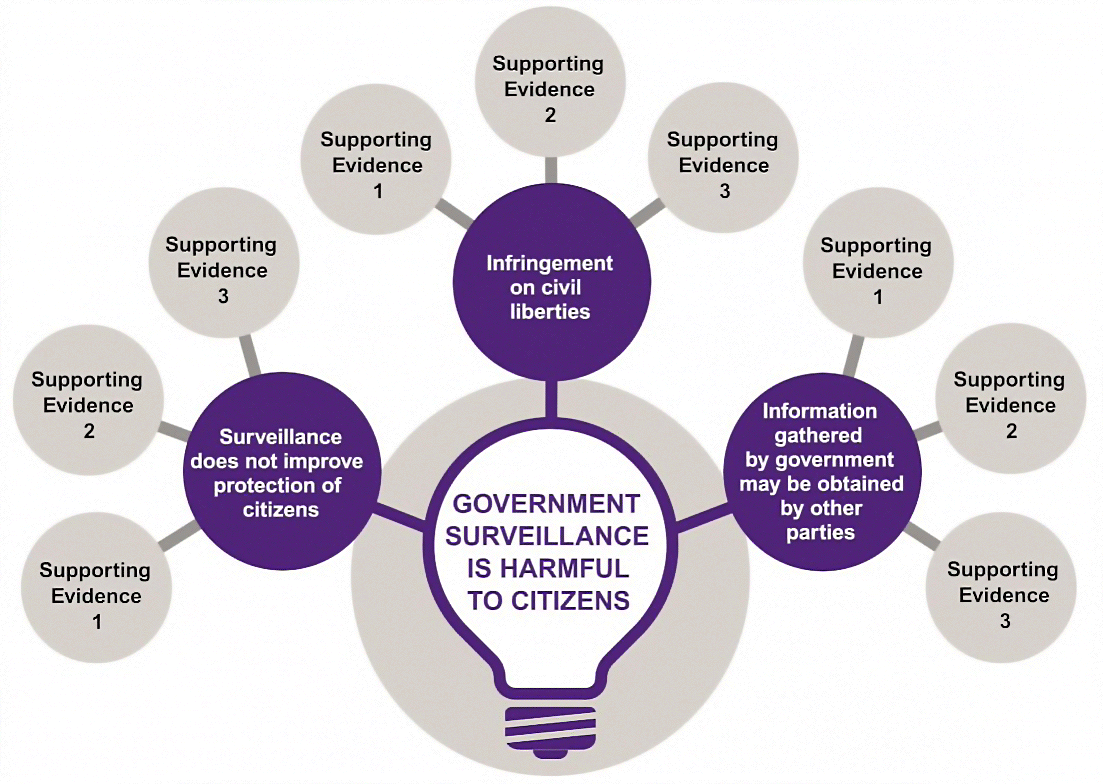

The body paragraphs are where you make your case to the reader that your thesis statement should be supported. You do this by presenting a series of arguments (generally one per paragraph) that are backed up by evidence from other sources. If appropriate to your topic, you may also make recommendations based on the evidence and the arguments that you have presented.

You may find, in the process of writing your body paragraphs, that you change your mind about what you think about the topic, or what conclusion you want to draw. Changing your mind is perfectly acceptable - in fact, changing your mind in response to new information is one of the best things that you can do! Changing your mind may mean going back and adjusting your thesis statement to say something slightly different, but it is better to do this than spending lots of time writing something that you eventually don't find convincing after all.

Body paragraphs tend to follow a predictable sequence that outlines your arguments, evidence and recommendations in a clear, logical manner.

In each body paragraph of your essay, you should:

1. State your contributing argument. Your contributing argument (see diagram, purple circles) is the statement that you are trying to convince the reader to be true, or the action that you are trying to convince the reader should be taken. If you completed a concept map during the planning phase, it will be written there.

2. Provide contextual or background information needed in order to make any upcoming evidence make sense.

3. Present evidence (see diagram, grey circles) in the form of statistics, short quotes, research findings or specific examples and explain how this evidence supports your argument.

4. If appropriate, make a recommendation of what should be done, and why it would work (if your contributing argument is that an action should be taken).

5. Show how the evidence that you have presented links back to the thesis statement.

The topic sentence clearly states the writer's argument.

The writer then provides some background information to explain their argument in more detail, in this case by showing that they understand what has been done by the government so far.

In the next sentence, the writer presents some evidence from an external source that helps to make their case (i.e., the government's online efforts won't reach people who don't have the Internet).

In the next couple of sentences, the writer clearly uses the evidence just presented to recommend a logical course of action.

Note that towards the end of this, the writer includes another piece of evidence to further strengthen their case.

The final sentence links the recommendation back to the paper's thesis statement.

Tone in academic writing

is a term borrowed from music. In music,

tone relates to the setting of the instrument

so as to create a certain feeling or mood,

and it's pretty similar for writing.

You can see that sometimes things might be written

in a light-hearted or informal tone, but

you can also see that, in academic writing,

the tone of the language used is more formal.

This distinction is important for effective communication

and, in building an appropriate professional relationship

with the academic reader.

Research has shown that teachers and tutors are

particularly critical of student writing that

does not conform to an academic tone.

So, it's really important to write appropriately

for your intended academic audience.

In order to maintain a good academic tone,

there are a few key things to avoid.

First, it's a good idea to avoid making

very broad generalisations about the topic.

For example, "Parents asking their children to pay rent

is always wrong."

It might well always be wrong,

but we don't want to say it like that.

Another tip is to avoid using sweeping adjectives.

For example, "The findings from previous research

are obviously biased in favour of older people."

A further tip is to avoid the use of

overly emotional language.

For example, "Oh, it's just heart-breaking

to see the effects of this disease."

Finally, another good tip is to avoid

the use of inflammatory statements.

For example, "Smith's paper was terrible and he

doesn't deserve to call himself a researcher."

Let's take a look at an example of something

written in an informal tone, and then take a look at

how it can be improved to a more academic tone.

"Yo, when I got my students to think science was

wicked cool, their test scores went through

the roof! When I asked for their spin on

the improvement, they just said

the test felt like a piece of cake."

Now, here's the same information,

but expressed in a more academic tone:

"When I was able to engage my students

and get them interested in science,

their test scores improved significantly.

I asked a few students why they thought

the scores had improved, and they

admitted that the tests seemed much easier."

The activities contained in this module

will help you to recognise the language features

involved in maintaining a formal academic

tone in your academic writing, so as to

meet the expectations of academic readers.

WHAT IS METADISCOURSE?

Metadiscourse (meta = a level above; discourse = discussion) is a technical term used to refer to words and phrases that explicitly signal the reader about what is happening in the text. An assignment that has many metadiscoursal elements used throughout it will generally be easier to understand and more pleasing to read.

There are two main categories of words and phrases that make up the metadiscourse of an assignment. These categories contain words that indicate:

When constructing a piece of academic writing, there are

- How the text is structured; or

- The attitude or commitment of the writer to an idea.

times when you may want to explicitly signal to the reader

exactly what it is that you are doing, or thinking. You may wish,

for example, to indicate that you are moving on to your next

point, or that you are uncertain about how well a piece of

evidence supports your thesis statement.

We say that these sorts of signals-to-the-reader are part

of the metadiscourse of the text. Skilful writers use the

tools of metadiscourse to convey their meaning to the reader more

clearly, and they do this in two main ways.

The first way is to provide signals to the reader about the

organisation and structure of the text. This involves using

words and phrases that indicate some sort of change in the flow

of the text. Let’s look at a few examples.

When making a series of points or arguments, you may wish to

use sequencing markers like “Firstly”, “Secondly” and

“Finally”.

You can also use transition markers like “As a result,”, or

“Consequently,” or, “On the other hand,” that you can use to jump

from sentence-to-sentence, from point-to-point, or from

paragraph-to-paragraph.

If you want to jump from one idea to another, you can flag

this for the reader with a topic shift, like - “Turning now to…,”

or, “It is also important to consider…”

You can signal to the reader that a paragraph or section

has a particular purpose with an announce goal. You can do this

by saying something like “In this section, my aim is to…”

If you're citing the work of someone else, an evidential, like -

“According to Smith in 2012…” - this can be used to indicate that you are about to

present the ideas of another person.

Finally, there are basic code glosses, like “for instance,” and

“for example,” that indicate to the reader that you are about to

illustrate your argument with a specific case.

Using these phrases can guide your reader through the entire

text from beginning to end in a way that's coherent

and easy to follow.

The second type of metadiscourse is that in which you select

and use phrases that explicitly signal your commitment

or attitude toward the things that you’re writing about.

For example,

When you want to strengthen your commitment to what you're

you’re trying to say, you might use boosting devices, such

as “Obviously”,“Clearly”, and others.

On the other hand, if you want to be more careful about the

points that you’re making in your writing, you might use a

hedging device. These are expressions like, “It is

possible that…” or, “This could be the reason why…”

Engagement markers are used when you want to urge the reader

to take a specific action. To do this, you might use phrases

such as, “We need to…” or, “The public needs to understand…”

Finally, you can self-insert into your writing, using

personal pronouns, such as “I”, “we” or “our”. It’s a common

misconception that these pronouns should be avoided in academic writing,

but studies have shown that writers actually use these

features a lot in published research, when they want to

strengthen the points that they are making.

The activities in this section will help you improve your skills

in the use of metadiscourse.

Comments

Post a Comment